POCD (Paedophile OCD)

Of all of the OCD subtypes, POCD, also known as Paedophile OCD, is one of the most distressing. It leads normal, caring people into an endless battle with their own thoughts. In this article, I am going to explain exactly what POCD is, why it is absolutely not the same as real paedophilia, and how we can treat it using Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention (ERP).

I’ve covered everything that I describe here in this video, so check that out too.

POCD and the intrusive thoughts that come with POCD are NOT the same as a paedophilic attraction. They are entirely the opposite in fact, and I’m going to show you why. Because of the very nature of POCD, people who suffer from it tend to keep their symptoms to themselves and avoid getting help.

This is understandable.

However, I want to show you that POCD works in just the same way as all of the other OCD subtypes such as Harm OCD, Contamination OCD, Scrupulosity OCD, etc., and is therefore treatable in just the same way. For example, in Harm OCD an individual becomes obsessed with the possibility that they will act on an intrusive thought of attacking someone, such that they experience excessive anxiety, spend much of their time in their heads trying to convince themselves otherwise, and avoid triggers like knives, family members, violence on the TV etc. Swap the thoughts of attacking people with knives for sexualised thoughts relating to minors and we are now talking about POCD.

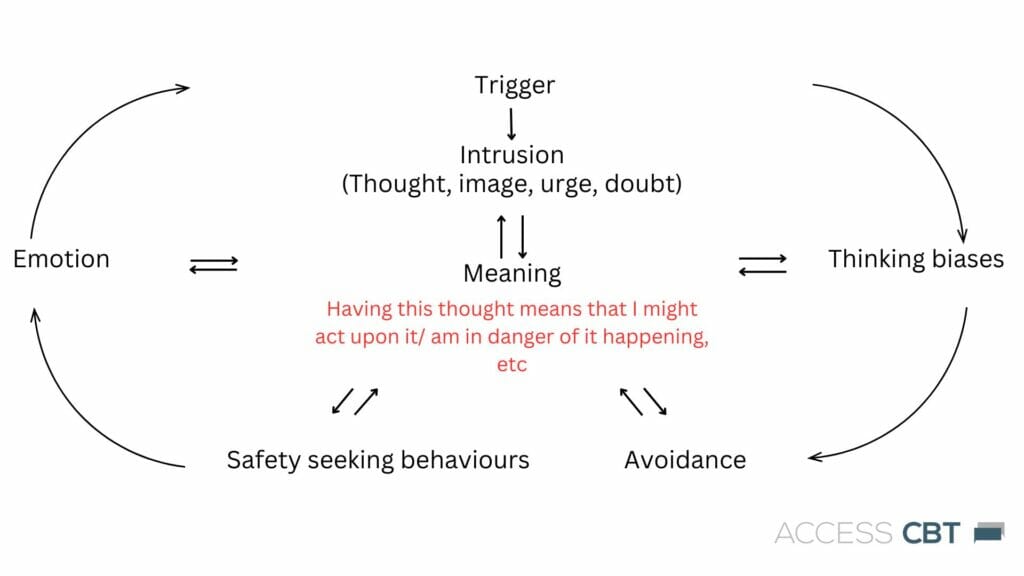

In OCD, we over-estimate the significance of having had the thought. We think that because we have had an intrusive thought that this says something bad about us, that the thought can lead to us taking unwanted action and that we must do everything possible to stop it from being true. I’m going to show you how this all works in a generic Cognitive Behavioural model of OCD, before digging into how this relates specifically to POCD.

Cognitive Behavioural Model of OCD

This is the model that I use to treat OCD and all of its subtypes. The model states that it is the interpretation of what it means to have had an intrusive thought that leads to emotional distress. This is turn leads to unhelpful, ineffective, and life-limiting cognitive and behavioural attempts to get rid of the thought, disconfirm the (inaccurate) meaning attached to it, and alleviate the emotional distress. When these strategies don’t work – I will explain the psychological reasons for this later – our OCD sufferer then becomes obsessed with trying to get rid of, understand, reduce the effects of the intrusive thought more and more. These obsessive efforts get in the way of normal functioning – we can’t work, enjoy our spare time, or spend time with our families and friends – and we have full blown Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

At the top of the model, you can see that we have an intrusion, or intrusive thought. This can be in the form of an image, thought, doubt or urge. Now, it’s important to highlight that intrusive thoughts of all kinds are commonplace in people both with OCD and without. It’s just that in OCD, we treat our intrusive thoughts as though they are a threat to us. For more information on this, take a look at the video I made here:

We then have the part headed “Meaning.” This is the most fundamental part of our OCD model, our target for change, and what makes the difference between people who develop OCD compared to those who do not. In OCD, people interpret the intrusive thought as being something which they may act upon, are a bad person for having had, and is something that presents a risk to themselves, the people around them and their future.

If we believe something is a danger to us, our brain automatically activates a “Threat response” – more on this later – which makes us feel the emotions of anxiety, fear, disgust, irritation amongst others. In response to this, we will then use lots of safety seeking behaviours to get rid of the thought, reduce our emotional distress, stop us from acting on what we believe the thought means, and get life back to normal. The problem is that these behaviours typically don’t work, or only work in the very short term. As an example, reassuring myself that I won’t harm someone will make me feel better and a sense of relief. But what happens the next time I get the thought – I now have to do more reassuring. The safety seeking behaviours have the effect of maintaining the meaning that we attribute to our intrusive thoughts – e.g., “The only reason I didn’t make everyone sick was because I washed my hands seven times” – and get reinforced because of the actual short term relief that they give.

The next element of the model, “Avoidance”, is again something that maintains the meaning of our intrusive thoughts. If the meaning I give to having had an intrusive thought about stabbing my wife is, “I might act on this thought, I’m a danger to her and probably everyone else”, then avoidance kind of makes sense. If I try to avoid knives, my wife, and thoughts about killing people, and my wife is still alive, then something must be working, right?

Wrong.

The problem is that the avoidance maintains the belief. How will I ever find out if I am a danger to people, or if these thoughts are as “bad” as I think they are, if I avoid triggers all of the time? In OCD, we overcome the problem by, in a reasonably graded way, reducing avoidance.

The last part of the model is Thinking and attentional biases. This refers to all of the glitches, biases and distortions that inhabit our thinking that can make us interpret aspects of our experience in ways that don’t fit the reality. For example, we may engage in emotional reasoning, which is a thinking error in which we make a judgement based upon how we feel emotionally. This means that someone may feel the emotional state of anxiety and interpret this as being evidence that they are in danger of acting on the thought. The problem is that anxiety will come and go and just having a feeling does not mean that something will happen behaviourally.

Another thinking bias is predictive thinking, which is the literal belief that we know what is going to happen in the future. You don’t. I don’t. The idea that we know what is going to happen next is an illusion and to change our behaviour or apply meaning to predictive thoughts would be an error. Applied to OCD, predictive thinking could be something like, “my future is ruined.” Belief in this would make us feel despairing, hopeless and perhaps less likely to engage fully in CBT therapy and some of our more challenging exposure tasks. No one know what is going to happen next, even if we believe that we do. If we did, then those lottery numbers would be easy to pick and we would all be driving around in Ferraris.

So that’s the basic Obsessive Compulsive Disorder model. Now, before I make it specific to the POCD model, I’m going to talk about two concepts which are essential in distinguishing POCD from real paedophilia.

The first concept which I’m going to introduce is what we call “Ego Dystonic”. Ego Dystonic means that the reason we are so anxious, threatened and/or disgusted by the nature of our Intrusive thoughts is because they go against who we view ourselves as being as a person. If your values and lifestyle are consistent with being a kind, loving, friendly person, then the very fact that we have had an intrusive thought that goes against this creates an internal conflict. “Here’s me, a good dad/mum/nan/teacher/etc, living a positive life, and I’ve had this horrible, disgusting thought – What’s going on with me?”

The intrusive thought is Ego dystonic. If the thought conflicts with our inner nature, then understandably we will pay a lot more attention to it and want to fix/understand/get rid of it. We see the intrusive thought as a threat to our sense of self which then leads to activation of the threat system. Very clearly, this is what is happening in the case of POCD. The very fact that the person who has a POCD-type intrusion appraises that thought as being against who they are as a person, places the problem clearly in the realm of obsessive compulsive disorder.

Our POCD sufferer isn’t happy that they have had these thoughts (as we would expect a true paedophile to be), they are instead reviled, disgusted, and incredibly fearful because that intrusive thought has popped into their head.

A typical example of this ego dystonic confliction is in the case of New Mothers. POCD has been reported in new mums who, despite loving and doting on their new baby, experience an intrusive thought of a sexual act towards their child. Because this thought runs so opposite to their values of being a loving parent, our new mum becomes fearful that the thought may happen again, and that it might make them a risk to their child. Of course, they are not a risk whatsoever – they care deeply for their baby. But their initial appraisal of the thought as being a potential for them to cause harm means that the thought itself is viewed as a threat. This leads to activation of the threat response. When the threat response is activated, we experience emotions of fear, anger or disgust, and our brain and body becomes primed to both deal with, and look out for the threat. Since the threat in OCD is a thought, our young mum then organises her behaviour around either getting rid of the thoughts or minimising the potential for them to cause harm to her baby. This leads to increased dysfunction in the form of avoidance (e.g., trying not to look at the baby when changing their nappy), mental compulsions (e.g., checking inwardly for signs of emotional attraction or physical arousal or constantly reassuring themselves that they are not a bad mother), or safety seeking behaviours (e.g., not wanting to be alone with the baby). The problem is that these efforts only maintain the idea that a thought is something to be feared and avoided, which keeps the POCD going.

So that’s just one illustration of how POCD thoughts are ego dystonic (remember that phrase) and entirely different to true paedophile thoughts. The next illustration also looks at how POCD intrusions are experienced differently to other thoughts that we may have. For this, we highlight the difference between “Desire” and “Fear of Desire”.

If you’ve ever struggled with an Intrusive thought before, whether it’s a pocd thought, or other type of OCD intrusion, try this exercise. Think of something that you know that you really enjoy, crave or desire. Foods are a good example of this. Do you like Cake, Chocolate or Strawberries for instance. Now take a moment to imagine this food. Really focus on what it looks like in your mind, how it smells, how it tastes. Now notice how this feels at an emotional level. What does it feel like to have these thoughts about something that you know you really desire? My guess is that you feel positive feelings, openness to the thoughts, and maybe even imagine how you’re going to get some of the food later.

Now compare this experience to how you feel when you have an intrusive thought. How do you feel emotionally when you have an intrusion? What do you think? What do you do? I imagine that your response is quite different to thinking about cake. You may feel anxious or disgusted. You likely want to push the thought away and try to avoid ever having a thought like this ever again.

What do you make of this exercise? Do you notice the difference between something that you genuinely desire (Cake, Chocolate, Strawberries) and something that you fear? Understanding the difference between Desire and the Fear of Desire is really helpful in enabling us to get leverage on our intrusive thoughts and helps us understand the difference between a POCD intrusion and a paedophile thought. You don’t desire your POCD thoughts, you fear them. A big, important difference.

So, we have established the concepts of “Ego-dystonic” and “Desire vs Fear of Desire” and how they clearly distinguish POCD from true Paedophilia. With these factors in mind, I’m going to re-introduce you to our CBT model, but tailored to include symptoms which are specific to POCD.

This is an example using a made-up but representative client. The trigger is taking their grandchildren swimming, and the intrusive thought is of touching a child inappropriately. In the early stages of therapy, I always to great lengths to emphasise that intrusive thoughts are commonplace in both clinical (people with OCD) and non-clinical (without OCD) populations, and it’s a literal feature of our minds to just throw out content all of the time. Our minds are spitting out between forty thousand to sixty thousand thoughts every single day and we dismiss the vast majority of them – they barely even touch conscious awareness. However, there are certain types of thoughts which we perceive as being problematic for us.

In our example, our person takes their grandchildren swimming and their mind just spews out one of these sixty thousand thoughts, which is an image of them touching a child. Rather than just dismissing it as an unpleasant thought that means nothing and getting back to swimming with the grandkids, they instead apply another meaning to it “Thinking this thought must mean something bad about me – I’m a paedo, and my life is ruined.” This appraisal is what takes an intrusion from being just an unpleasant thought to something that activates a threat response and the rest of the OCD symptoms. The appraisal might include imagery of acting on a thought, being ostracised by society and being on the news as a sexual predator. Belief in this appraisal, which itself is just another thought, activates the threat response which leads to them fearing further thoughts like this and leading to changes in their behaviour to get rid of the thought and to stop the thought becoming true.

The Threat response is an emotional system which is hardwired into our body to enable us to deal with danger and enhance our chances of survival. It was vital for our ancestors to survive in dangerous environments and is exactly what you need today if a bus is coming towards you or someone is coming at you waving an axe. You may have heard of the “fight or flight response”. Your threat system helps you to deal with danger by giving you the physical and cognitive resources needed to fight or flight (and a couple of other responses) and stay alive. One of the problems with our threat system as it works for us today is that it will also overestimate threat and try to detect it when it isn’t there. In the case of OCD, where the threat is a thought and therefore an aspect of the brain itself, the part of the brain most involved with the threat system (the amygdala), will prime itself to look for the thought (the “danger”) in situations where it may have seen it before. Simply, our amygdala will be looking for the “bad” thought, from which our thinking brain will say, “This thought?” The cycle then repeats, maintaining the fear – intrusion relationship.

Because of the misappraisal of the intrusive thought, our person then engages in avoidance and a set of safety seeking behaviours (compulsions). They avoid taking the Grandkids swimming and start avoiding the school run. Both of these avoidant behaviours then lead to the problem of not being able to disconfirm their appraisal of the intrusive thought. Their life becomes more limited, providing greater opportunity to focus on their obsessions.

We see that their compulsions involve mental reassurance (“I really am a good grandparent, I really am”), checking for signs of emotional attraction or physical arousal, and checking memory for signs that they have not done anything untoward. Checking for signs of arousal is unhelpful because we will pay attention to physical sensations that are normal and always there (your brain filters out most of the sensory content in your body most of the time) and will misinterpret them as evidence that we have “felt” something. There is a big difference between normal physical sensations and arousal but the cognitive errors in POCD will latch onto the normal sensations and misinterpret them to support the feared meaning.

Likewise, revisiting memory to check if one has done anything untoward is also unhelpful because a) memory always has natural gaps and b) we can misinterpret these gaps as being the possible time when something bad has happened. With memory checking, the job is never done because there is always gaps in memory that we can revisit and scrutinise – I’ve covered the problems with checking memory in the following video:

How I treat POCD

The first thing that we do is identify just what the problem is, and we do this using a Cognitive technique called “Theory A vs Theory B.” This technique asks you to identify just what it is you are trying to solve with your overthinking, avoidance, compulsions, etc. Are you trying to solve the problem of being a paedophile (Theory A) or your fear of intrusive thoughts about becoming a paedophile (Theory B)? We establish what the evidence is for each of these theories and then begin creating exposure and response prevention exercises and behavioural experiments to test out which of these theories is more accurate. One example of this would be watching a TV advert in which there are children. Now, if your problem was theory A, then we might predict that you would enjoy the advert, and feel comfortable with the exercise. But, if your problem is actually theory B, then we would expect you to become distressed, panicky and want to avoid the video.

When we start to test your theory A vs theory B, we start to get leverage on just what your problem actually is. From this, we can then start to practice dropping more and more of your compulsive behaviours and avoidance, which in turn changes how you appraise your intrusive thoughts. If we no longer fear our intrusive thoughts, then guess what? We pay less attention to them, our amygdala looks out for them less and we get fewer of them at a lesser degree of intensity. This is how we get you back on track from POCD.

In conclusion

In this article, I have established how POCD (paedophile OCD) is part of obsessive compulsive disorder and entirely different to real paedophilia. I’ve also shown how patterns of behaviour such as compulsions, safety seeking behaviours and avoidance can contribute to keeping the problem going through maintaining faulty meanings of what it means to have an intrusive thought.

If you would like to start on a course of CBT for POCD, then contact me directly and we’ll get started.

George Maxwell – Accredited CBT and EMDR therapist and Positive Psychologist.